Nathan Ramsey's Trip to Ghana - October 2010

Nathan Ramsey's trip Ghana - October 2010

Dr. Nathan Ramsey is a graduate of the Marshall University School of Medicine. He is a member of the graduating class of 2011 from the emergency medicine residency at Palmetto Health.

SPONSOR: COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY MAILMAN SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH

WEBSITE LINK: www.mailman.columbia.ed

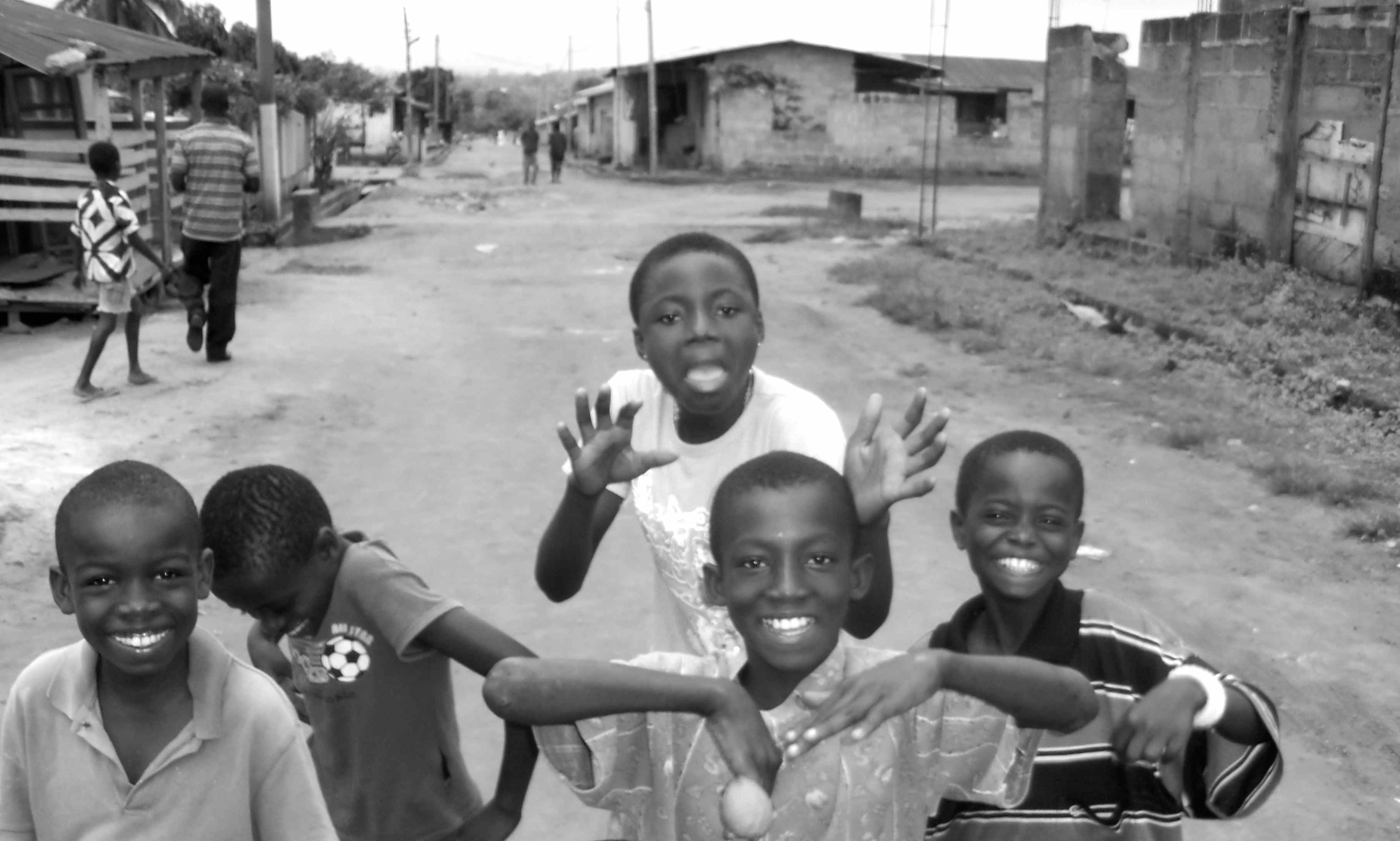

I traveled to Ghana, West Africa during the fall of 2010 with the SidHARTe Program sponsored by the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. I spent six weeks at a district hospital participating in an educational program. The goal of the program is to develop a curriculum and to focus on training mid-level providers the basics of emergency medicine. Emergency medicine is a developing specialty in Ghana. Most emergency care is provided in ill-equipped casualty units in district hospitals. The units are rarely staffed by physicians and the first-line providers are nurses and medical assistants (equivalent to physician assistants or nurse practitioners). Most of the nurses have not even been trained in the basics of emergency care.

This trip was a totally new experience for me and proved to be invaluable in that its primary focus was not direct health care delivery but rather to educate and to train local practitioners. It was my first opportunity to switch modes from a resident focused on learning emergency medicine to a teacher passing on what I have learned. I was stationed in a 100-bed district hospital located in the medium-sized city of Ashanti- Mampong, Ghana. There was one staff physician for the entire hospital and, for the most part, I functioned independently during my time at the hospital. I worked as an attending doing daily teaching rounds as well as giving weekly lectures, leading small group sessions, and running mock patient simulation.

This was a very rewarding experience in the fact that I realized that the time I spent in Ghana would have an impact even after I left. By training local practitioners we can make a difference that lasts long after the brief time spent in their country. There is potential to affect the care of countless patients that one will never meet.

I have posted some excerpts from my journal of the trip to help you get a flavor of what practicing in Ghana was like.

Day 2:

I arrived in Accra, Ghana.

An airport worker let me skip customs, then, later expected a bribe [I gave him $20].

An aggressive taxi driver tried to get me out of the airport before my ride and additional travel arrangements could be made. I found my real ride to the hotel.

I exchanged US dollars for Ghana cedis on the street. All the money changing offices are closed on Sunday. The guy I changed money with was remarkably accurate and honest. I felt a little like a gangster to trade over $800 on a sidewalk. 1100 cedis is a huge wad of cash.

Day 3:

I arrived in Kumasi. I had to wait 2.5 hours to be picked up at the airport.

My unofficial orientation was interrupted by a RTA between a police officer and a man on a motor bike.

The biker was a multi-trauma with positive FAST scan (blood in the abdomen) and hypotensive (in shock). I did the best impression of ATLS I could and we sent him off to the larger hospital that had a surgeon. It was 1 hour ambulance ride away. The policeman had a dislocated shoulder. This was the first time I have had an AK-47 in the trauma bay.

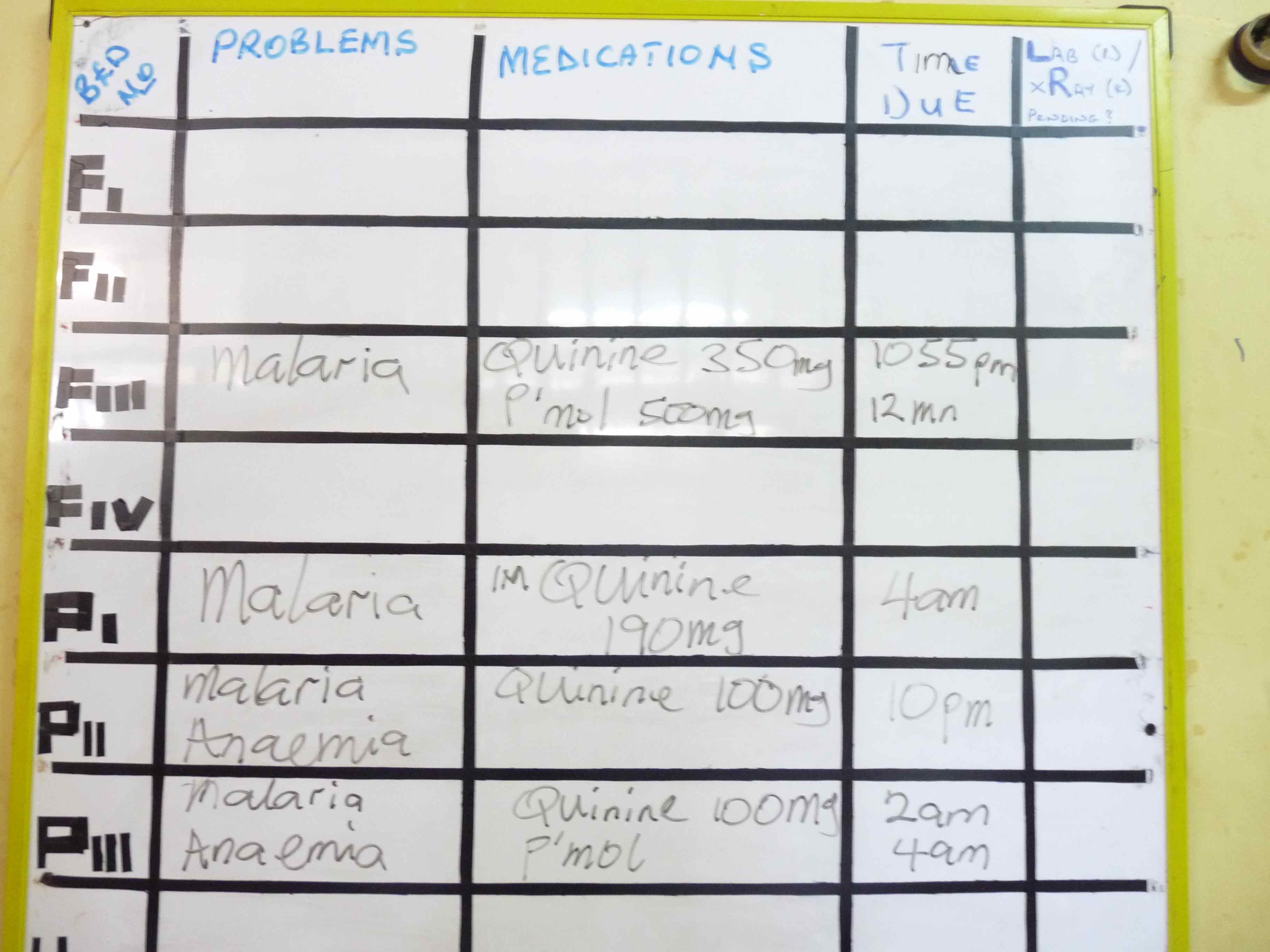

Today, I saw my first cases of malaria ever. I realize this is going to be a totally different experience than I have ever had in my life.

Day 7:

One of the patients I cared for yesterday died overnight. The family of a baby we had been treating for meningitis decided to take their child home against medical advice. She was in the process of dying this morning despite our best efforts. A second family of an infant of less than one –year-old decided to take their child home as well. He had cerebral malaria and was neurologically devastated. He likely will die with or without treatment.

Day 14:

I was able to diagnose a young man with a perforated ulcer. This was the first time I have successfully used a flat and upright abdominal x-ray to find free air in the abdomen. I looked at the films and there it was as plain as could be – a free air bubble under the right diaphragm. I suspected perforation but had only seen those x-ray findings in textbooks.

Medicine here is like taking a step back in time. This must have been what it was like practicing medicine in the years following World War II. You have to depend on your brain, history and exam findings more than sophisticated diagnostic testing.

Day 16:

Tonight a man came into casualty seizing. We quickly determined he was a diabetic with a very low blood sugar. The entire hospital was out of Dextrose 50% Solution which was the indicated treatment. We improvised by giving him a rapid infusion of 1.5 liters of Dextrose 5% Solution. This was successful in resolving the seizures. We then realized the hospital was out of oral glucose. I ran back to the house and dumped a whole box of sugar cubes [including some ants] into a cup. I then added just enough water to dissolve the sugar into a gel. I rubbed this into the patient’s mouth. He eventually recovered enough to be able to drink the rest of the solution. When I left for the night he was talking and alert.

I learned today the hospital is out of D50, Insulin, IV pain meds, Urine test strips, and I’m sure countless other vital medications and equipment.

After regular hours the x-ray technician turns off his phone. So, x-rays are only available from 9am to about 3-4pm.

Day 21:

Today was one of the hardest days yet. I work at least 8 hours in the casualty unit today. When I walked in this morning it looked like a battlefield hospital. There had been a serious vehicle crash involving fifteen people. Six of them were present in our unit including two critical trauma patients. This was a hard task for me and one nurse to take care of. The nurse on duty was not a casualty nurse. She was filling in from the women’s and children’s ward. Every bed was full including hallways. Emanuel stayed late and Sulu came early to help out. The power was out for at least four hours and unfortunately the backup generator was out of gas. No labs were available during this time and I was not able to read the mornings x-rays until 6pm. This was a true mass casualty incident for our small hospital. The casualty ward is usually only staffed by one nurse. We eventually transferred three patients to KATH hospital. No one died under my care today. That was a real blessing.

Day 26:

I accidently stood on an ant colony and got bit several times by African ants.

We intubated our first child in the casualty unit today. He was a one-year-old having status seizures. We had to give him so much medication to stop them that he needed to have ventilator support. I went with him in the ambulance to KATH hospital in Kumasi. I had to use an ambu-bag to ventilate him in route. We went lights-and-sirens all the way which is about an hour drive. The ambulance driver was amazing. He dodged in and out of traffic coming within inches to other cars. At one point we went the wrong way down a major four-lane road weaving in between on-coming cars. This may have been the most dangerous thing I’ve done in my life. I still feel a little car sick from my ambulance ride.

Day 28:

We left for Mole Park today. We made it all the way by the grace of God. The roads were the worst I have ever traveled. There was a three-hour stretch spanning 90 kilometer that was more like off-road conditions. Our driver’s name was Badu. He was very skilled and we only got stuck in the mud one time. We were able to get out relatively easily. We were driving in a taxi and saw no other cars attempting the trek. We encountered only SUVs and trucks. I was very nervous that we might break an axle or get stranded in the mud. Our trip took about nine hours total.

We went to a local monkey sanctuary. The monkeys were so friendly we could feed them from our hands. The locals treat all the monkeys as pets. They believe that if they harm a monkey it will bring a curse on them and that someone in the village will die. They even bury the monkeys when they die. The monkeys come into the village to participate in breakfast, lunch, and dinner on a daily basis. There were no less than twenty monkeys that we feed bread as we walked along the trail.

The rural villages are very poor. They mostly consist of crumbling mud huts.

We spent the night in an old guest house located in Larabanga which is just outside the park. We tried to sleep on the roof but a rainstorm drove us inside.

Day 31:

I had fufu with light soup for the first time today. I learned that the one of the ingredients is a root that is poisonous if it is not cooked and prepared properly. It was good but I like rice ball better.

We had a man come in today with a devastating hand injury from a homemade shotgun that misfired. It basically destroyed half of his hand.

Today was very busy with traumatic injuries. We transferred three patients to KATH and had one man come in with a devastating head injury that we are managing with comfort care.

Day 36:

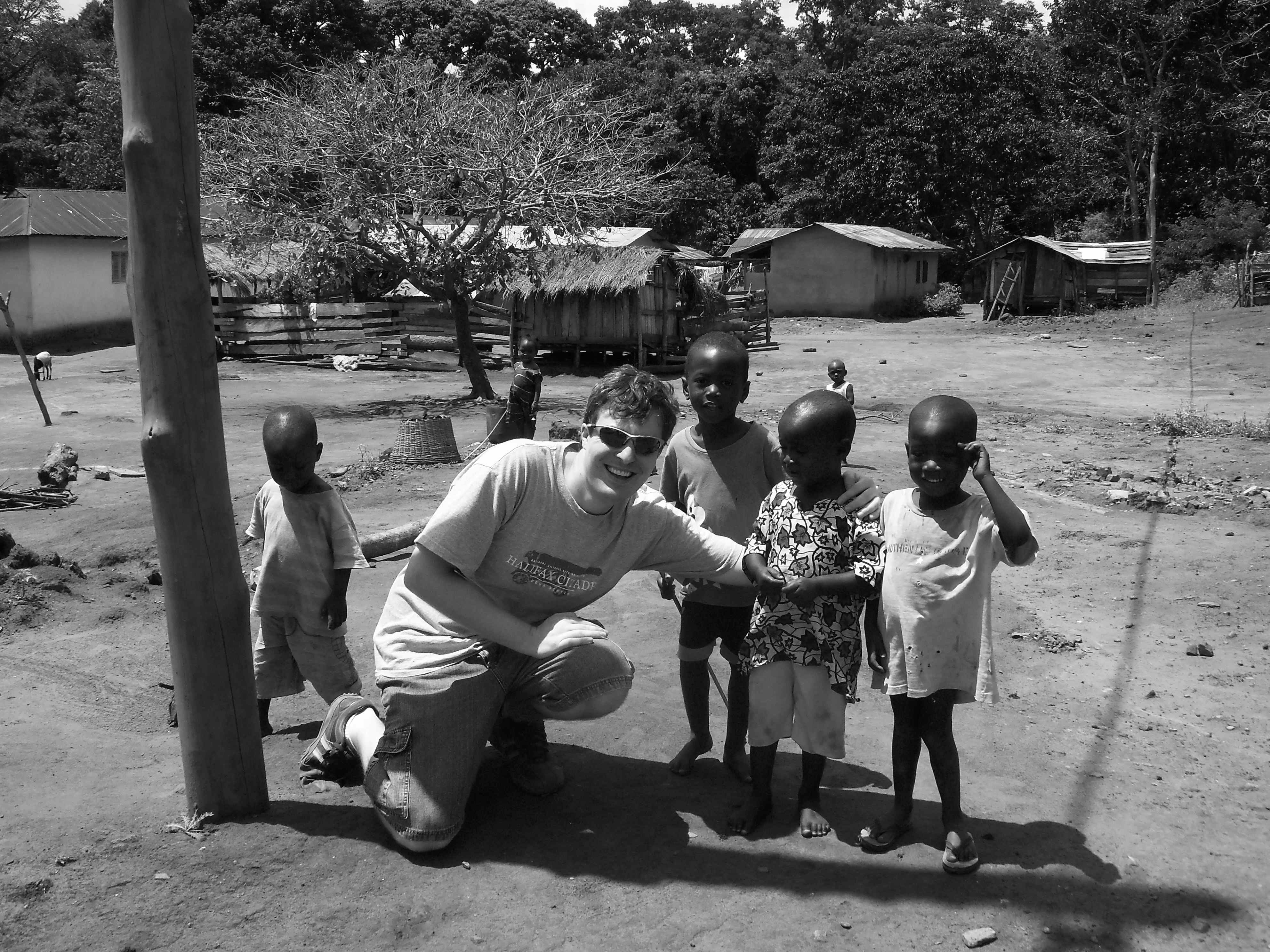

Today we took our first solo trip to Kumasi for some touring and shopping. Everybody in Kumasi knows my name. They yell Obruni whenever I walk by. Obruni means white man.

Kumasi is a disorganized city with a mass of humanity and activity. We spent a good portion of the time lost wondering around the streets. We ate lunch at Big Baboo’s which is a restaurant that serves white people food. It was nice to get a little taste of home. We toured the palace of the king of the Ashanti Empire. We learned about the culture and history of the region.

Day 41:

Today was my last day working in Ghana. It is very sad to leave all the friends I have made here. I spent the day saying a lot of goodbyes.

I packed this evening. My bags are much lighter going home than when I arrived. I left all of my slacks, most of my scrubs, and threw away all my socks because of the mud.

I’m sure is will take a few days to get adjusted once back in the USA. I’m looking forward to some American food and a hot shower once I get home.

Back to Locations List

Back to Locations List