Haiti - Jon Virkler 2012

jon virkler, md - HAITI, SPRING 2012

Dr. Virker graduated for the University of South Florida School of Medicine. He gradauted from the emergency medicine residency at Palmetto Health in 2012. He lives and works in Palm Beach, Florida.

SPONSOR: PROJECT MEDISHARE

http://www.projectmedishare.org

Arrival

Arrival in Haiti is a stark contrast from departure in Miami. After flying for just under two hours, I found myself transported immediately into the third world. To depart Miami I had my passport scanned by an electronic sensor and rode two moving sidewalks and a train to gate D55. To arrive in Haiti, I deplaned at one of the two gates in the only international airport in the country, walked down the steps from the airplane onto the tarmac, got onto a standing-room-only bus that took us to customs. Our bags arrived on the only baggage terminal in the airport.

International Airport

We left the airport as a group and fought through the throng of porters hoping for a tip of one or two American dollars, and packed into the back of two Land Rovers. We drove past streets lined with shops and tap-taps (pickup trucks as taxis) and pulled into the gates of Bernard Mevs Hospital, after being allowed to pass through the guards armed with shotguns.

Street from the back of a Land Rover

Armed guards at the gates

The Hospital

Bernard Mevs Hospital is one of many in Port-au-Prince, most run through relief organizations or Doctors Without Borders. Bernard Mevs is supported by the University of Miami, and staffed by a mix of volunteers and Haitian staff. The Haitian staff is incredibly willing to learn and eager to have American involvement, and there are also Haitian nursing students and medical students.

The hospital itself has a triage shanty (3 walls and some curtains), a two bed ED, a four bed ICU, a nine bed med-surg unit, and a ten bed spinal cord unit. There is also a separate pediatric ward which doubles as a PICU. There is an orthotic and prosthetic shop, outpatient clinics, three operating rooms, and an infectious disease ward of four beds.

The ER

Triage Tent

Operating Suite

The hospital has impressive capabilities for Haiti. It has several adult ventilators and a BiPap machine for use in the ICU, and has the only pediatric ventilators in Haiti. There is onsite Xray (sometimes), and a CT scanner. The CT scanner only works occasionally, as it runs on city power (which is frequently down), and staffing is spotty.

There are surgeons on call for general, orthopedic, neurosurgery, and Ob/Gyn. Medical and pediatric admissions are handled mostly by the volunteer physicians. Sometimes capability or bed availability necessitates transfer to outlying hospitals. This is difficult because these either have a poor reputation (The General), or are in areas of town even the Haitians are hesitant to drive to.

Emergency Medicine in HAITI

Many of the simpler complaints are handled in the triage tent by the nurses, paramedics, and Haitian doctors staffing that area. The more serious complaints are brought to the ER for resuscitation, where most equipment is fairly available.

Patients are initially screened at the gate by an armed guard and a translator. Their chief complaint is presented to the triage doctor or ER doctor and the patient is allowed in or told to leave.

Common complaints include vomiting and diarrhea, febrile illness, and traumatic injury. There is significant street-level violence in Haiti and so stabbings, assaults, and head trauma are common. There are also no traffic laws, and so pedestrian injuries and motor vehicle collisions are frequent. HIV is also rampant, and the sequelae of this disease are frequent. Other serious pathologies I encountered included eclamptic seizures, respiratory failure, PCP pneumonia, stroke, pneumothorax. There were many machete assaults and other simple lacerations as well.

Often the CT scanner does not work and frequently Xray is unavailable as well, leaving you only physical exam and an old Sonosite ultrasound machine. Ultrasound is incredibly useful for everything from cardiac and pulmonary exams to biliary and musculoskeletal complaints. Using ultrasound, I diagnosed pneumothorax, long bone fracture, volume overload from renal failure, liver metastasis of gastric cancer, appendicitis, and many other conditions.

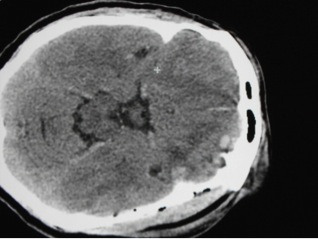

Epidural Hematoma

Life in Haiti for a Volunteer in haiti

Volunteers are typically not allowed outside the gates, except for a nightly trip to the United Nations, which has a restaurant. These provide a nice respite from the stress of running a third-world hospital, and allow a nice return to American food (as opposed to the normal fare of goat, chicken, and rice). The local beer Prestige is cheap and drinkable, and flows freely at the UN.

UN Excursion

There are some comforts, but for the most part the complex definitely feels like the third world. There is wireless internet available, meaning you can chat or Skype with family back home. The showers are abysmal and there is no hot water. The drinking water is unsafe so all drinking water must be filtered. The mosquitoes and heat are intense, even in March, and the air conditioning works well but infrequently. A week deployment feels long when you are in the midst of it, but when the week reaches its end you realize you want to stay. Haiti grows on you, and the Haitian people especially. There is definite need, and Bernard Mevs does well to meet that need in harsh circumstances. All told, it was one of the best experiences of my life.

For more information about the organization I worked with on this global health mission, go to Project Medishare at:

http://www.projectmedishare.org/

The night shift ER crew

Sunset over Haiti

Back to Locations List

Back to Locations List