2017 Himalayan Health Exchange - Baker and Hardy

Mobile clinics at high altitude

Sponsoring Organization: Himalayan Health Exchange

Zach Hardy, MD (pictured left) is a graduate of the Texas Tech School of Medicine and Daniel Baker, MD (pictured right) is a graduate of the Medical University of South Carolina. Both are members of the Palmetto Health EM Class of 2019.

The Himalayan Health Exchange elective in the Himachal Pradesh region of India was a totally unique opportunity that allowed me a chance to see a part of the world that I had never experienced before. The patient population that we were charged with seeing has very little access to medical care, if any, throughout the year and due to their remote location we would travel on foot too all of their villages to provide this care. Admittedly, the fact that we got to spend all our off days hiking through the Himalayas, coupled with the night time views of the Milky Way and more Indian food than we could ever imagine, made the trip quite an unforgettable experience.

After over 24 hours of flying from Atlanta we finally made it to Leh where we met our team. The flight from Delhi to Leh was incredible as we were able to watch the mountains begin to peak out through the clouds giving us our first view of the Himalayas. We landed in Leh, a small town in Himachal Pradesh, and met with our companions while we recovered from our flights and attempted to quickly adjust to the altitude.

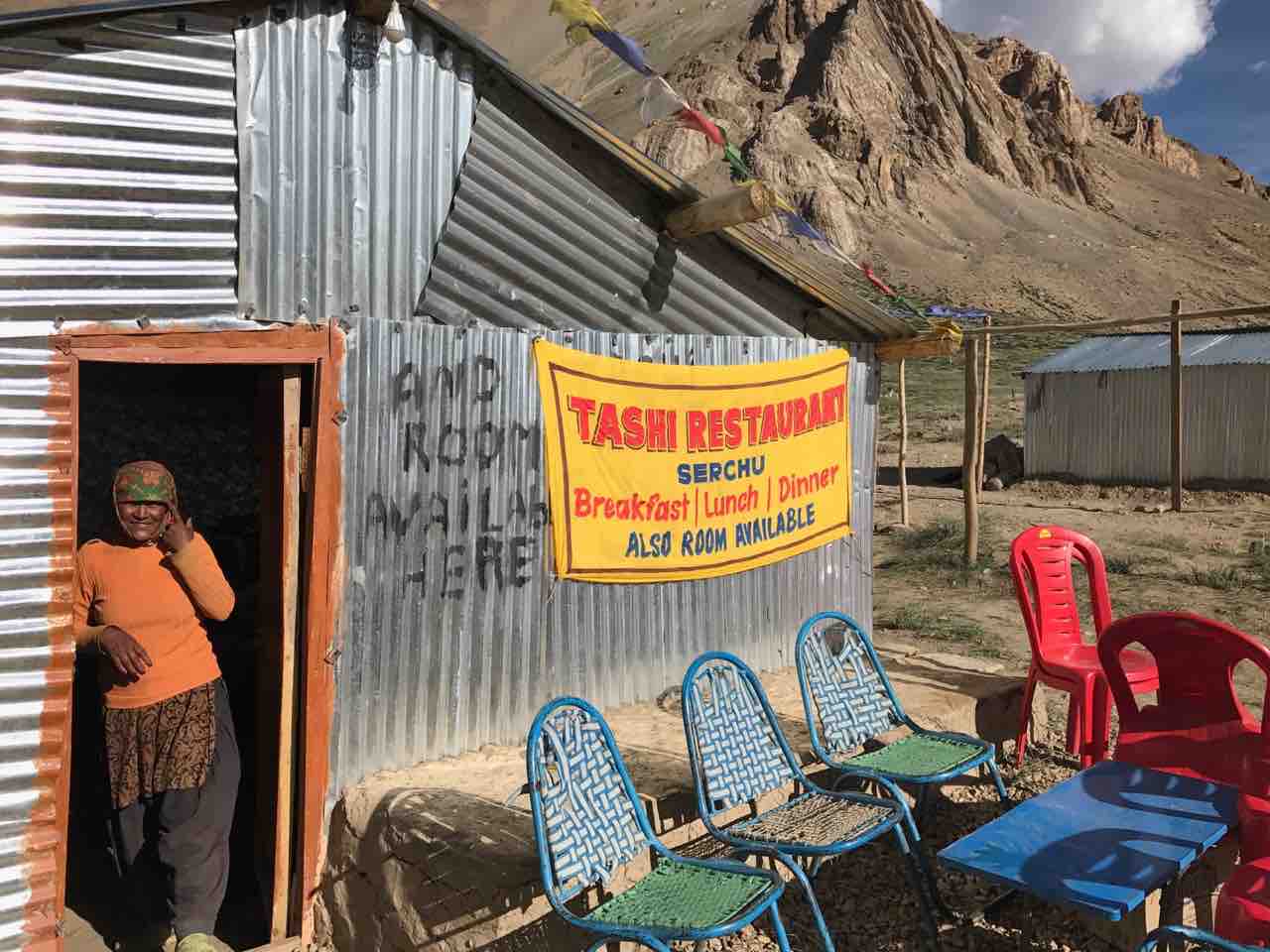

We left Leh the next morning to drive to our first clinic site, Sarchu. The road to Sarchu consisted of nine hours of cringe-inducing single lane roads bordered by treacherous drops. On this drive we crossed the Taglangla pass (17,582ft), the second highest pass in the world, according to the sign at the top. This rapid elevation gain led to a number of our team feeling the effects of altitude sickness, so we were happy to make it down to the relatively low elevation of Sarchu where we would be camping (13,500ft). Sarchu itself consisted only of about 50 yards of shacks set on either side of the highway. Each one had a big sign reading the same offer: “Breakfast Lunch Dinner. Bed available!”.

Our first clinic day was an eye opening exposure to the challenges of providing healthcare in remote settings. We were limited significantly in our ability to both diagnose and treat by the minimal stock of tools and medicine we had available to us. The majority of patients presented for GERD, eye complaints and chronic musculoskeletal issues. Many patients we saw in Sarchu were road workers who had only come to the area for work. The uncertainty of follow-up care weighed heavily on our decision process. These decisions were only going to become more difficult as we had to decide what limited supplies to pack and bring on our trek for the next three weeks.

The next day, we packed up our camp for the first time and headed out on foot with a local monk “Lama G” as our guide. We hiked for the next 5 days, working our way towards the Phriste la pass (18,250ft). It was quite a momentous achievement when we crossed as, for most of us, this was the highest elevation we had ever reached. Sadly, we were only allowed 10 minutes at the top to enjoy the accomplishment and take pictures before descending so as not to develop altitude sickness. On the other side of the pass we dropped down into the valley where we would spend the next two weeks.

Going into the valley felt like being transported back in time. Each village we came to consisted of less than 100 people. The lifestyle they lead is incredibly physically demanding. They would work from sunup to sundown performing physical labor such as carrying bushels of grain or making mud bricks by hand. They worked with only minimal tools and relied entirely on the glacial snow melt for irrigation and drinking water

In clinic it was apparent how much this lifestyle took a toll on their health. Nearly every older woman we saw had diffuse chronic pain from carrying these heavy loads on their back for so many years. We saw a man in clinic who had presented for dry eyes and was hoping to obtain sunglasses. However, we noticed he was walking with a limp so we asked to take a look at his leg. When he pulled up his pant leg we were shocked to see what looked clearly like a complete knee dislocation. Apparently he had injured it in a fall 30 years prior and had walked with that limp his whole life.

After each clinic day we would gather around for didactics. Each of us had prepared a 15-20 minute lecture that we would present and then discuss with the group. These topics helped us place into context the issues we were seeing as well as ones we were looking for. We discussed topics including altitude related disease, rheumatic fever, sexually transmitted diseases, peptic ulcer disease, acute hepatitis A and more. In addition, we had enlightening conversations discussing the ethics of medical missions as well as the social issues and dynamics of India.

In total we had 9 clinic days and saw over 300 patients. We were able to help with a variety of acute issues including eye irritation, GERD, musculoskeletal pain, as well as viral and bacterial infections. We also found several possibly worrisome findings including a man with possible Tuberculosis, a young man with what seemed to be heart failure and a women with signs of liver cancer. While we were not able to do much for them in the field, hopefully we were able to help somewhat by having them follow up in the city for further evaluation. Overall it was an amazing experience that showed both the positives and negatives of global health while getting to work with a great group of people.

Back to Locations List

Back to Locations List