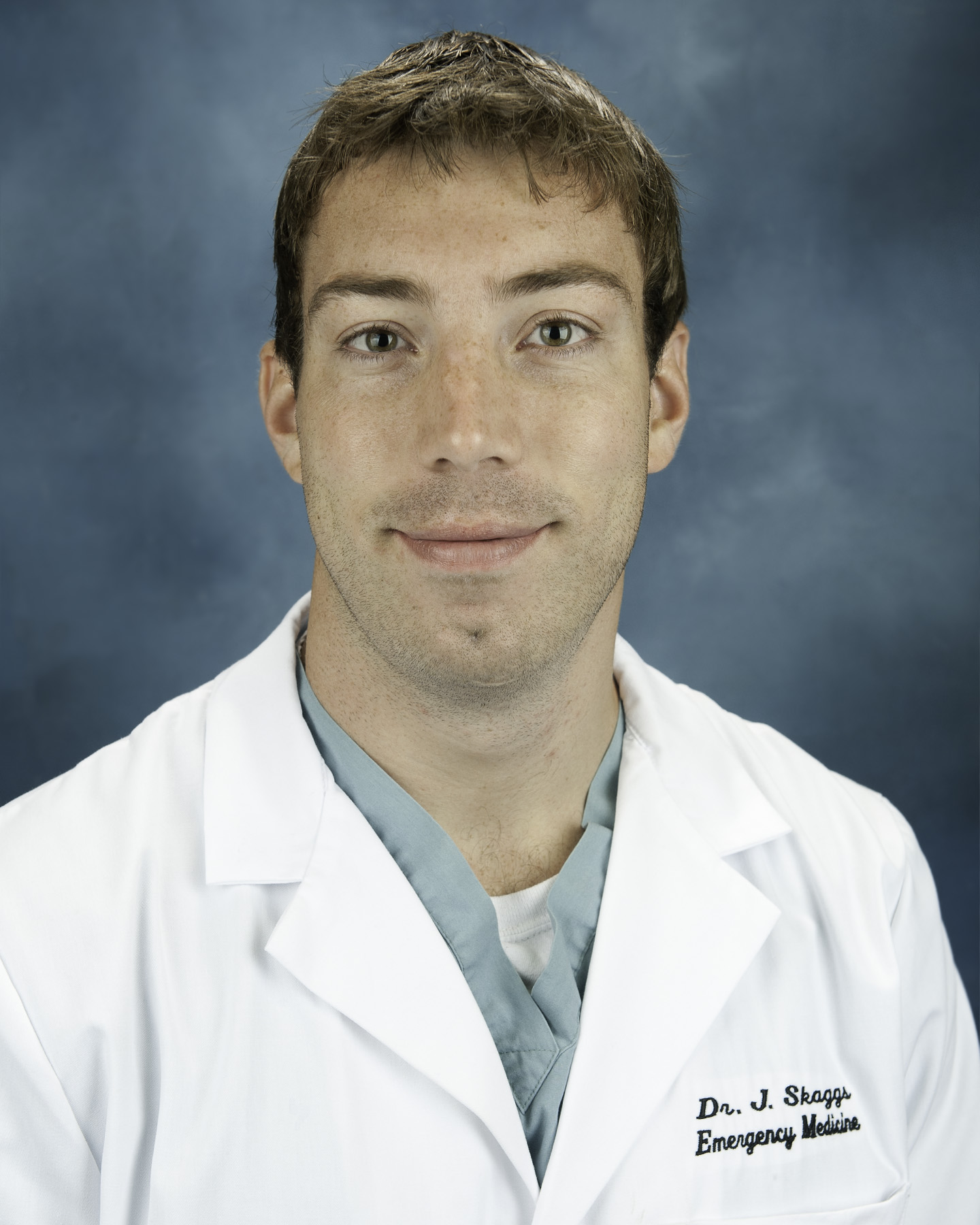

Josh Skagg's Mission Trip to Sudan - February 2013

JOSHUA SKAGGS, MD - CLASS OF 2013

SUDAN, AFRICA

Dr. Skaggs was raised in Africa. He attended the University of South Carolina School of Medicine and was a member of the graduating class of 2013 at Palmetto Health.

In January / February of 2013, I spent a month in East Africa on a Medical Missions trip. The purpose was to work in South Sudan, one of the most undeveloped, isolated, and devastated countries in the world. It was an incredibly tough yet very amazing experience.

I just wanted to give a little background on South Sudan to those interested:

South Sudan and Sudan used to be under the control of Egypt, and was overseen by Great Britain. In 1956 Great Britain withdrew from Sudan, its former colony. At that time Sudan had two regions, the Arab north and the tribal south. War soon broke out, with the northern Sudanese government began killing all non-Arabs in the south who would not ‘convert’ to Islam. The south subsequently formed an autonomous region in an effort to protect itself. Through the decades, multiple wars continued until South Sudan seceded from the north and established its own country in 2011. Unfortunately, fighting still continues in the disputed border area between the north and south today. Not only has civil war decimated this country, but in the Darfur region in the west, Islamic militias, known as Janjaweed, invading from neighboring Arab countries and deriving support from the northern Sudanese government, have killed hundreds of thousands of the indigenous black Africans in this area. Also various rebel groups, such as the Lords Resistance Army (LRA), have invaded from neighboring countries to take rob and enslave the local populace.

South Sudan, due to decades of civil war, as well as ongoing corruption, is one of the least developed countries in the world. South Sudan has the highest per capita rate of victims of human trafficking and slavery. Over the last decade an estimated 2 million people have been killed and 4 million people have been captured and forced into slavery, predominately in North Sudan. While the former Sudan is almost one quarter the size of the USA, South Sudan today has less than 25 miles of paved roads, very few schools, and the hospitals are in name only.

Prior to starting the Medical Missions trip, I was able to swing by Ethiopia for a few days and visit my dad, step-mom, and little brother, who live in Addis Ababa.

Also while in Ethiopia I was able to take a helicopter trip with my dad to the lowland area of Ethiopia, to visit some isolated tribes with which my dad was working. An American pediatrician accompanied us as well, and brought some basic wound care supplies and medicines for any medical cases that we might encounter while on the trip.

After a few days in Ethiopia, I headed to South Sudan. Getting to South Sudan in itself is a struggle. The only way to get into the country is through Ethiopia or Kenya. Juba, the capital, has a paved runway, but nowhere else in the country does this exist. Our team flew in on 2 separate flights on a single engine prop plane. To get to our final destination, we had to make 3 different stops to refuel on the way. Once we arrived at our final destination, we were greeted by some soldiers. Their way to examine our bags once we arrived was to pick the bag up in the air a few feet and then drop it – I guess they thought if we were carrying explosives or weapons, they would be able to tell once the bag exploded!

The group I went with is called Make Way Partners. MWP is a Christian group that tries to rescue children, typically in 3rd world countries, who are at a high risk of slavery or death. The organization got started after the founders, who were missionaries in Spain, came across large groups of young children in Portugal who were held hostage for sex slavery. The reason MWP got involved in South Sudan is due to the huge number of orphans there, many of whom died to a lack of food and shelter. For example, in one region in South Sudan, literally hundreds of orphans were dying because they were getting killed by hyenas at night. MWP has to date founded 4 orphanages in South Sudan, with each placing taking care of several hundred kids.

There is a huge prevalence of orphans in South Sudan. There are many reasons for this. The country has been under civil war for decades, and a large percentage of the middle-age / elderly population has simply been wiped out by war. With diseases like AIDS, TB, and Meningitis ravaging the population and an absolute lack of health care, this has contributed to many orphans as well. Sometimes the parent will not be able to feed all the children, and will have to decide which one to abandon in order to see if they can at least keep some of their children alive. Finally, cruel cultural practices are responsible as well. There have been many children kidnapped and sold into slavery from the South into the Arab North. Even if these children are to get free and return home, the families will not take them back, as they feel like they have become a disgrace.

Typically us doctors and nurses in the group would work in the clinic all day, then in the evening would get together with the orphans and play soccer or volleyball. The kids were amazing - despite some absolutely awful stories from these kids of literally watching their parents and siblings get killed in front of them, they were some of the most loving, fun to be around children. They loved attention, and you couldn’t walk more than a few steps anywhere outside without a young kid running up to you, grabbing your hand, and walking with you. Oftentimes when walking back from the clinic I would walk with 4 or 5 kids all holding my hand at once.

Our living conditions at the orphange: there was barely enough rooms / bunk beds for the orphans themselves, so in order for us not to intrude, we slept in tents outside. It was brutally hot – our first week was in Torit, in the south of the country, with temperature hovering around 110. Week two was in Nyamlell in the northern edge of the country, in the Darfur region, which is the edge of the Sahara desert. Temperatures could climb as high as 120 there.

Where we all crashed at night.

The view from my tent.

Filtered water, obtained by diffusing through clay pot

Our bucket showers

We had a truck that would bring in our water from the local river, whereas the surrounding villages would have to make do via donkey transport.

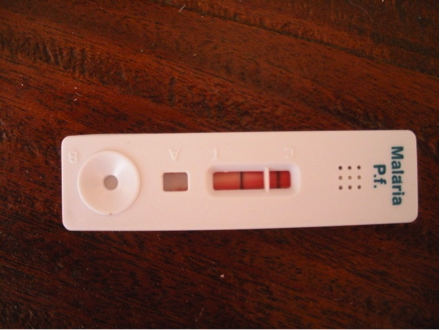

We saw patients out of the clinic attached to the orphanage. There was no diagnostic equipment other than a rapid diagnostic test for Malaria Falciparum, which was actually quite handy – a drop of blood in the device, apply a reagent, and have a positive or negative test result back in 5 minutes. We did have a very well stocked pharmacy however.

South Sudan has one of the highest infant mortality rates in the world, according the CIA factbook, getting narrowly edged out by countries like Afghanistan and Somolia. From what I heard there was one ObGyn in the entire country, located in the Capital. Caesarean sections are obviously hard to come by. There are again some incredibly shoddy local practices related with childbirth – for example, after the umbilical cord is cut after birth, feces is used to rub into the umbilical stump. It seems to live to the age of 5, you really have to beat some serious odds. Typically in South Sudan, there are midwives in charge of certain regions that will come and deliver a baby. One of the things we tried to do was get together with the local midwives several times during our stay, and educate them about the delivery process and what to do / not to do in some of the more common cases that they might encounter.

There are regional hospitals spread out throughout the country, staffed by people who simply don’t have the training or the support to be able to take care of the many sick patients they see. The hospital I visited had a couple primary care doctors who acted as Internists, Surgeons, Ob Gyns, you name it. The patient’s family members had to supply the patients with food, clean them and take care of them, and purchase medications if they were prescribed (and if they were even available).

Here is a picture of the general ward in the local hospital.

There are no ventilators, no electricity (except when generators would run for a few hours in the evening), and no such thing as general anesthesia. Operations would all be done using regional / local anesthesia.

Onto some cases that I saw while working out of the clinic…

This was a patient who likely had visceral leishmaniasis. He was dying from the disease. My fingers are palpating the edge of his spleen.

This is a poor child that had what I believe was atopic dermatitis – he had it so bad that his eyelids were contracted, keeping him from being able to blink. He was developing corneal clouding already due to the inability to close his lids.

There were lots of tumors that we saw. This growth on the knee had been there 10 years, had not changed in size, and was not bothering the patient. It was quite firm, maybe a calcified suprapatellar bursa. The growth on the ladies arm had significantly increased in size recently, was thought to be malignant.

There were tons of kids with burns, from being around cooking fires at their homes.

Onchocerciasis - River blindness

Another common cause of blindness – Trachoma, an easily treatable disease, which causes the eyelids to invert, will scratch and ultimately scar the cornea. Here you can see an entropion secondary to C. Trachoma.

Pott’s disease, secondary to extra-pulmonary tuberculosis

Thought to be secondary syphilitic lesions.

This lady’s conjunctiva was pure white. Her hemoglobin had to be around 2. She was so weak she couldn’t walk without assistance. She had been having dark stools, and likely had a chronic GI bleed from hookworm. There are no blood transfusions available in South Sudan [outside of the capital], so I treated her parasites, gave her vitamin C and iron supplements, had her drink fluids, and that was all we could do.

Enteric Worm

There was tons of malnutrition. One of our responsibilities was to check kids Mid-Upper Arm Circumfurance (MUAC), and weight them, and if they were severely malnourished, to report this to the local health authority. Unfortunately, the local health district / hospital didn’t have any nutrition supplements to feed even kids that were starving in front of them.

A lot of the kids had Kwashiorkor syndrome as well as hair color changes due to protein / nutritional deficiencies.

This poor kid spontaneously developed these lesions a couple days before I saw him. Treated him for staph infection.

Another sad case of a child who had a history of epilepsy, had a seizure, and her foot fell into the fire while seizing. Not only did she have a badly burned food, with exposed bone here, but due to her history of epilepsy the village ostracized her because they thought she was under a curse. She obviously had a lot of trouble getting around, and we didn’t have crutches, so we tried to help her get around by using a chair to hold on to and put in front of her.

Dr. Carol, an American surgeon from Alabama who lives and works in Kenya, as well as Dr. Seno, a Kenyan doctor who is doing a surgical residency under Dr. Carol, both came on the trip. They were absolutely fantastic people. Here they are amputating a gangrenous digit under the trees outside the clinic.

Here are Carol and Seno operating on a child that self-circumsized himself with his fingernails because other kids were making fun of his foreskin. His penis was badly macerated / infected, but he ended up having a good outcome.

There was a lot of ignorance when it came to disease. Here are some educational posters.

Here is the waiting room outside the clinic. People would begin lining up at 4am in the hopes of seeing a doctor! They would wait all day, until 6pm, and some would still not get seen. Out of the 4 doctors there, we would each see around 100 a day.

This was Amos, a Kenyan doctor who had been working in Kenya and South Sudan for 20 years. He has worked with many a NGO providing aid in South Sudan. During his work he has had planes drop bombs on him, has worked trying to save lives during meningitis outbreaks, during war conditions, and has about seen it all. An incredible resource to have on the trip.

Here are all the kids peeking in during clinic hours. Privacy was simply unobtainable.

A typical South Sudanese six-fer. Because no one had seen a doctor in years, the moms would bring all their kids in to get looked at. A couple observations – this mother is in her mid 30s. The South Sudanese live such tough, brutal lives that they appeared so much older than they were. Another challenge would be the mothers would uniformly tell us that their child has been having fevers, headaches and myalgias. I’m sure that they did due to the extreme conditions they lived in and lack of basic human necessities, but malaria was endemic in the region and also presents similarly. It was hard to tell which kids were there simply to get looked at by the doc versus which ones actually had serious pathology.

Typical kids reactions when seeing the scary bearded white doctor!

A couple of the orphans who would help me translate throughout the days. These kids were trained in the orphanage to speak English, Arabic, as well as local dialects, in addition to their Math, Science, and all their other classes. They were fantastic.

It’s hard to tell from this picture but the thermometer says 106. The ambient temperature, even in the shade, would cause the thermometer to climb so high, that every time I wanted to check a patient’s temperature I had to shake the thermometer to get the mercury below 98.6 before I could try to take a temperature.

This was on our last day – we all gave an address to the children, thanking them for their hospitality and allowing us to come visit them.

Here is [most of] the team, on our last day.

Thank you to all you folks who helped me and supported me through this experience!

Back to Locations List

Back to Locations List