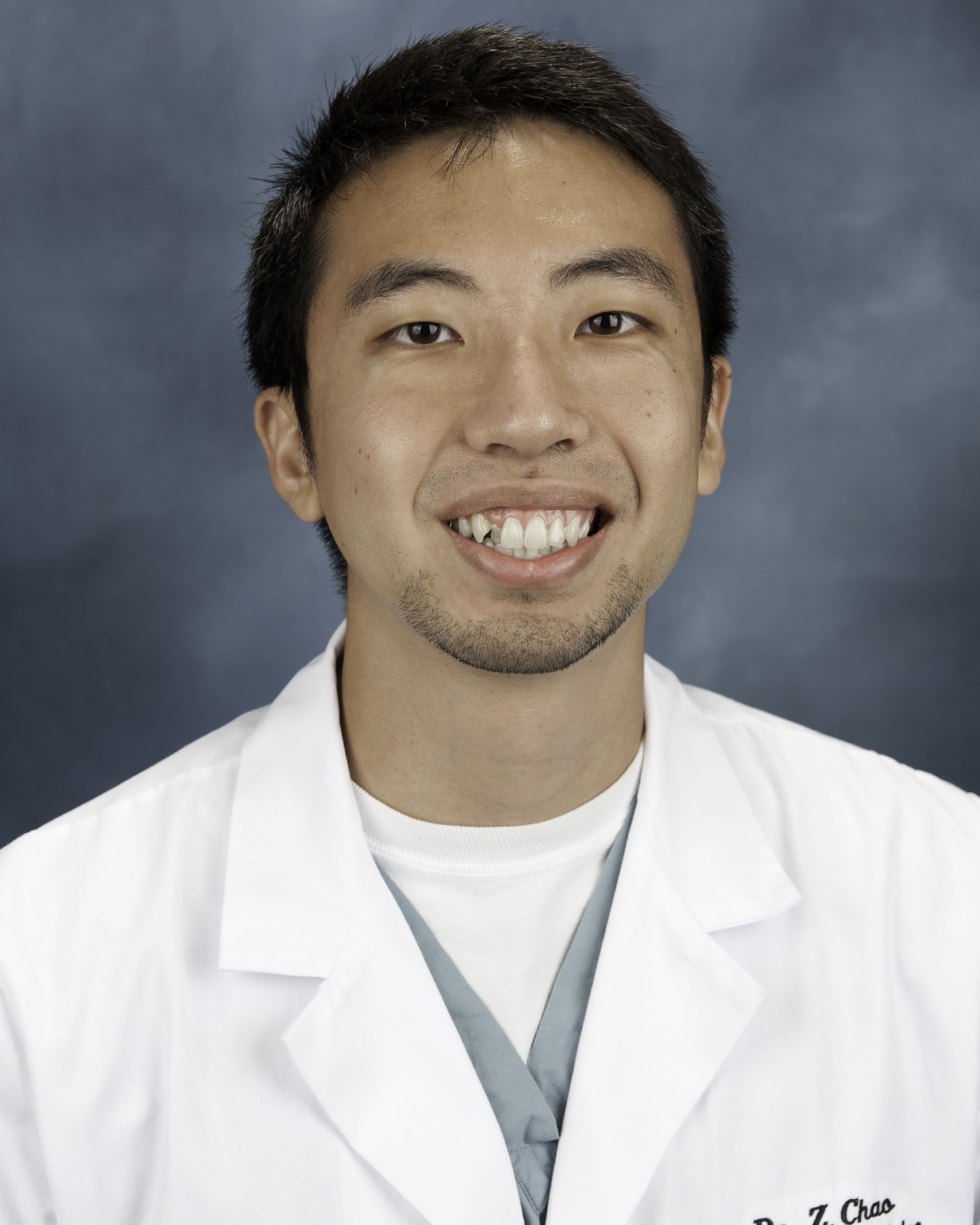

Zubair Chao's Rotation in Chendgu, China

ZUBAIR CHAO, MD - CHENGDU, CHINA, AUGUST 20112

Dr. Chao is a graduate of the Georgia Health Sciences School of Medicine in Augusta, Georgia. He is a graduate from the emergency medicine class of 2013 at Palmetto Health Richland.

SPONSOR: WEST CHINA HOSPITAL, CHENGDU, CHINA

WEBPAGE LINK FOR WEST CHINA HOSPITAL: http://eng.cd120.com

Towards the end of my second year our program director, Dr. Cook, was invited to West China Hospital to give a talk about point-of-care ultrasound used in the ED. Prior to his trip, we worked on translating one of his courses into Chinese to see if the healthcare providers in China would be interested in learning more about ultrasound. His talk was a great success, and he was invited back the following year, with arrangements made to host a Point-of-Care Ultrasound course as well. With the help of a resident from China, all the courses were translated into Chinese. Finally, in July 2012, we escaped the dry heat of South Carolina to land in Chengdu China, home of West China Hospital.

West China Hospital

Introduction to West China Hospital ED

West China Hospital was founded in 1892 and has grown to become a large tertiary referral center for all of western China. With about 5,000 beds (and overflow capacity to accommodate even more), nearly 100 operating suites, and a large outpatient center that sees 10,000 patients a day, it is considered by some to be the largest hospital in the world.

ED Triage Area

Main Entrance to Emergency Department

The Emergency Department at West China Hospital recently moved to its new home in a larger, more modern facility. The department sees an annual patient volume of about 160,000 patients, which is about twice what we see at Palmetto Health Richland. They have about a dozen attendings and over 30 residents, plus rotators. The Emergency Department is divided into a fast track area (“treat ‘em and street ‘em”), observation area (low acuity), secondary rescue area (moderate acuity), primary rescue area (high acuity/coding patients), and an EICU (Emergency Intensive Care Unit). There is also a debridement room for procedures and a trauma area. There are also operating suites located in the ED, but they are not currently on-line, as they have no staffing available. Patients who come to the ED -- the majority by private vehicle, only a few by EMS -- are first seen in triage, where they are referred to the appropriate location depending on their acuity. Also found in the ED is a cashier and pharmacy; with a fee for service model, patients pay a-la-carte for tests, procedures and medications.

Ultrasound Course

We spent the first week in China teaching the ultrasound course, with lectures and workshops for attendees to practice their skills. This course was a great success, and after its completion, I stayed for an additional month to work in the emergency department. I spent my time rounding with the teams in the morning and in the afternoons I took the residents of the particular unit I was in around to practice ultrasound scanning. Once a week, I gave a presentation on a particular area of ED point-of-care ultrasound (bedside echo, FAST exams, etc).

Observation Unit

English Morning Report

My first official week was spent in the observation unit. The day started at 8 am with all the residents, attendings, and nurses crowding into a lecture hall for daily morning rounds. Each unit in the ED gave a quick report on the events that transpired over the past 24 hours, plus information on any interesting patients. The unique part about these rounds was that they were delivered in English on Wednesdays and Fridays. In fact, one of my roles there was to help the healthcare providers improve their English proficiency during this exercise.

Rounding in the Observation Unit

After morning rounds and checkout, I reported to the observation unit. The observation unit at West China hospital fulfills a role that we do not really have in the U.S. Most patients seen in this area of the ED are those we would simply send home for followup in America . However, since the primary care sector is essentially nonexistent in China, these patients (including many who have travelled from distant cities to be seen at West China) are kept in the observation unit for a few days until serious pathology is ruled out. The unit also serves as a holding area for lower acuity patients until they can get a bed upstairs. The types of patients that I typically saw here had low acuity problems such as minor motor vehicle collisions, snakebites, gastroenteritis, sore throats, and symptoms like headaches and abdominal pain that required a cursory workup. There was also another fast-track area that I did not spend any time in, where patients were quickly seen and discharged.

Since many Chinese people (especially in rural areas) do not have access to hospitals, a lot of them seek practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine for their ailments. Consequently, physicians in China are much more familiar with herbal medications than healthcare providers in the West. For example, one week I saw numerous patients with snakebites whose first treatment of choice was an herbal paste (季德胜) that they slathered over the affected extremity with good results.

Herbal Snake-Bite Remedy

The observation area has the capacity to accommodate nearly 60 patients by doubling some of the beds with two seats. Some patients are kept there for days, and even weeks, as they wait for inpatient beds to become available. It is easy to imagine that many people get fed up with this scenario and would rather go home. As in America, these patients must also sign AMA forms to leave against medical advice prior to discharge. In addition to the number of people in the ED waiting for an inpatient room, I was told that there is a waiting list for those at home waiting for an inpatient room to become available; this list is 3,000-5,000 names long at any given time.

Two attendings were responsible for the 40-60 patients in the observation area, and each was responsible for a team of about 7-10 residents. Most of these residents were interns, though each team had one or two upper levels as well. I found it particularly interesting that I could immediately distinguish interns from upper-levels by the way they interacted with each other -- interns always looked a little lost and were questioned about findings they didn’t always have the answer to as the senior resident let them flail for bit before rescuing them, just like in America. Rounding took most of the morning, after which the team split up to accomplish their tasks for the day.

Flooding in the ED because of a busted pipe

Rescue Area

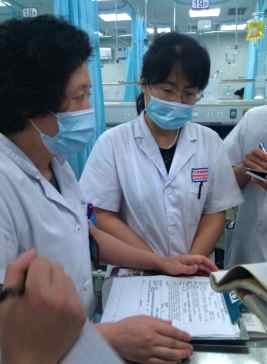

The rescue area was where many of the higher acuity patients were seen, and it was the largest and busiest area of the emergency department. It was split into primary and secondary rescue areas, the former having about 10 beds and the latter about 30. In reality, there were overflow beds everywhere. The 10+ beds in the primary rescue area were staffed mostly by 2-3 senior residents, who were also responsible for traumas that came in. Patients that were stabilized were moved to either the secondary rescue area or the EICU. The secondary rescue areas were similar to the observation unit in that there were teams that rounded. Here, a total of 3 attendings with a team of about 5-7 residents each rounded on patients. Many of the patients were essentially holds for inpatient beds. Unlike our hospital in the U.S., where admitted patients are managed by the admitting physician even if they are still physically in the ED, at West China all patients in the ED are were still rounded on and managed by the ED staff regardless of their admission status. As a result, patients are worked up with tests like rheumatoid factors, ANCA, and other tests I have not seen since my medical school days. Rounding in the secondary rescue area felt like rounding on the floor. The closest we ever come to “rounding” in our ED in America is when we “run the list,” which takes less than 5 minutes.

Ultrasound Scanning in the ED

Given its size, reputation, and resources, West China Hospital also serves as a regional referral center for both Sichuan province and much of western China. Many patients are transported there everyday by ambulance from other facilities. Many more are individuals who have heard of West China’s reputation and have chosen to drive from thousands of miles away to be seen, instead of going to their local hospitals. When I asked the doctors why this was the case, I learned that there is a shortage of physicians in China. At the same time, many graduates cannot find jobs. The reason for this paradox is that much of the physician shortage is in underserved rural areas. As in the U.S., these places have a very difficult time attracting physicians. The pay in these areas is also significantly less than in the cities. In contrast, rural areas in America offer some of the best paying jobs in order to attract physicians to relocate there. Therefore, the quality of physicians in rural China is not as high and medical licensing is not as standardized as it is in the U.S., so someone who has not finished residency or has not passed the certification exam can still get a job in a rural area. Practitioners of traditional medicine often fill the dearth of physicians. As a result, most patients do not trust their local hospitals and go to the big regional hospitals when they get sick. This leads to physicians in rural hospitals having less clinical experience, further eroding the public’s trust in them. Attempts have been made to encourage people to visit their local hospitals instead of crowding into the overwhelmed regional referral centers like West China. For example, we had many rural physicians rotating with us, so that they could gain more clinical experience and become more familiar with managing different diseases. The attendings in our department also visited our satellite campuses. Nevertheless, people still swarm to West China, oftentimes with unrealistic expectations.

Residents Working in the Emergency Department

One of the most interesting patients I saw was a 15 year-old boy transferred from a regional Tibetan hospital. He had been thrown from his horse and had a massive skull fracture with an intracranial bleed. He was about a week out from the accident and by the time he got to us, he was intubated and both pupils were fixed and dilated, which did not bode well for his ultimate diagnosis. His family still seemed to hope that we were going to cure him, and all that was required was stepping up the level of care by transferring him to West China. The physicians there told me that, unfortunately, this happens fairly frequently, and families are very disappointed when they find out that there is, indeed, nothing that can be done for their loved ones.

One afternoon, I stopped by the physician work area to ask the residents if there was anyone they needed scanned. “Yeah,” one resident said, “Could you do an echo on bed 35?”

Taking the ultrasound machine to bed 35, I laid eyes on a young man strapped down in the bed. He spat and drooled onto the towel-bib laid over his chest. Straining against his restraints, he fought to lunge at me as I approached the bed. I cautiously placed the ultrasound probe on his chest as he continued to spit and snap his teeth in an effort to bite my hand. I assumed he had some kind of psychiatric disorder and finished by scan; imagine my surprise when a passing resident said, "Be careful, he has rabies.” "WHAT?!," I thought, "Thanks, first resident, for leaving out that important piece of information."

Rabies is actually a very rare disease in the U.S.; on average, only 2 cases are reported per year. During my month in the MICU, I had a rabies case that was the first case in South Carolina in over 50 years. That particular patient was already in multi-organ system failure when she arrived to the ICU and was quickly intubated. It took a few days to finally diagnose her, and she was dependent on the ventilator, CRRT, and multiple other supportive measures. As a result, I never saw the clinical presentation of a rabies patient until I got to China. I will never forget the rabid patient spitting and trying to bite me. Rabies is actually fairly common in rural China; during my month in China, I saw 3 cases. Unfortunately, this condition is nearly universally fatal. Once the diagnosis is made (on clinical grounds and the history at West China), the family is informed, after which they take the patient home to die.

As in America, the ED at West China sees a number of suicide attempts. Many attempts are with ingestions -- notably paraquat. Never seen in the US (it is banned), paraquat seems to be the agent of choice for suicide in China and with ingestions above a certain threshold, it is inevitably fatal. We saw a few cases of paraquat poisonings a week. Treatment is usually supportive, as toxic doses lead to multi-organ system failure. There are experimental protocols currently being tested at West China using CRRT, but it seems that even this simply prolongs the inevitable.

EMS in China

Chinese Ambulance

During my week in the rescue room, I had a few chances to go out with the ambulance to respond to some calls. Instead of emergency responders like paramedics and EMTs, the chief residents took turns going out with a nurse. The ambulances are owned by the hospitals, and there does not seem to be a central command center, like the dispatch centers we have in the States. Most patients arrive by private vehicle, but every few hours or so, we would get called out. West China ED has two vehicles that are converted vans with a stretcher in the back, oxygen, and an EKG machine. A nurse brings a jump bag with some supplies to check vitals, check a blood sugar, etc. The doctor also has a jump bag with airway equipment and other things. My calls out included an elderly lady who had a syncopal episode while visiting her husband at one of our affiliated hospitals and an elderly man status-post a recent stroke which caused him to fall, hit his head, lose consciousness, and have subsequent confusion and altered mental status. . Once we took them back to the hospital, we tried to find beds for them in the rescue area.

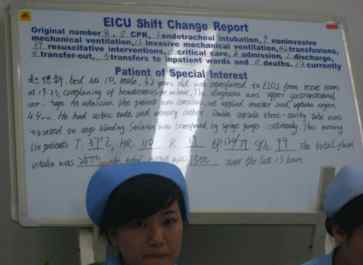

E-ICU

My fourth week in China was spent in the E-ICU. Due to ED boarding while inpatient beds become available, it makes sense to have a critical care unit within the ED to manage critically ill patients while they await an ICU bed. At our hospital in the US, we are able to provide ICU level care in the ED, but it takes up a valuable ED bed; fortunately, patients do not stay in the ED for days like they do in China. At West China, the EICU has 15 beds + 1 VIP room (private room with one-to-one nursing).

The majority of patients in the EICU are intubated. As in the US, EM residents usually do their own intubations, with Anesthesia as backup if necessary. Residents seemed very proficient from what I observed, and the patient population was also much easier to intubate than in the U.S. Patients I saw in the EICU included paraquat poisonings, septic shock (many caused by pneumonia), and GI bleeds from high rates of hepatic disease causing cirrhosis (I also saw a Blakemore tube used for the first time).

Since many patients in the ICU succumb to their illnesses, ED physicians are often required to have end-of-life conversations with their families. In general, I felt families seemed more accepting of death as a part of life, and once they were faced with the inevitability of death, they chose to take their loved ones home to die; the Chinese feel that it is better to die at home than in a hospital. Perhaps a part of this is the fact that healthcare services must be paid for. Physicians also are reluctant to pursue heroic measures in patients that are terminally ill.

One interesting case I had was a foreigner from the Netherlands who was visiting China when she developed abdominal pain and persistent diarrhea, and came into the ED in septic shock. She had a complicated past medical history of multiple abdominal surgeries for abdominal cancer and numerous other comorbidities. Fortunately, I was able to get on the phone with the repatriation doctor of the Netherlands, who had spoken to her primary care physician and specialists and compiled an extensive list of her past medical history and everything else we could possibly need. Moral #1 of this story: don’t get sick when traveling abroad. Moral #2: if you do get sick, be sure you have international insurance.

Death and Dying

The different ways in which families deal with terminal illness was another contrast I noted while in China. Although I was only there for a month, I noticed that families seemed to be more accepting when told that their loved ones' illnesses were terminal. They would often decline heroic measures and take the patient home to die. Cultural factors probably play as much if not a larger role in this approach as the high costs of an ICU admission for an intubated patient on pressors and heavy duty antibiotics would be prohibitive for many families. Regardless, this is very different from America, where patients often linger for weeks or even longer in the ICU, with many patients ultimately succumbing to their illnesses or, in cases of those who survive, going to a long-term skilled nursing facility.

Anesthesiology

During my last week in China, I bade the ED farewell to spend my last week in the operating rooms of West China Hospital where I would work on intubations. On my first day, I got 11 tubes and was reminded why anesthesiologists are airway experts – they do so many! After 2 years of ED residency, I feel fairly comfortable with most simple airways, but still dread the difficult airways. Given that we may go for quite a few shifts without an airway, I felt really fortunate to have this opportunity to spend an entire week refining my airway skills. I even picked up a few tricks for better bag ventilation while learning one-on-one with the anesthesia attendings.

The Chinese anesthesiologists preferred MAC blades; nearly every uncomplicated airway I did was with a MAC 3. They explained they only use the Miller blade for pediatric patients. For difficult airways, they tend to go for an Airtraq first. This is an intubating device purportedly invented by an Italian ED doctor that provides direct visualization of the vocal cords via a mechanism similar to a periscope. Once the cords are visualized, the preloaded ET tube is simply advanced along the track and it goes right in. I used it a few times and felt that it was bulky and not as maneuverable as the Glidescope, but I can see its appeal and definitely think that with some practice, it can be just as effective.

Tuesday morning, August 14, I was picked up at 7 am to accompany one of our ED attendings to an affiliated hospital in the countryside. From what all the residents were saying about this hospital, I imagined a tiny rural clinic. Instead, it was a 500 bed, 10-story hospital that had an ER with ambulance bays and surgery suites. I guess when you work in the largest hospital in the world, everything else seems like a rural clinic. There were a handful of residents at this affiliated hospital and it did not seem that the ER was being used to its full capacity. Even the floor beds were somewhat empty and the hallways seemed deserted. Given that the hospital just opened up 3 months ago, I hope it is simply a matter of time before people start going to it. In the back of my mind, however, I could not shake the image of empty rural hospitals as sick people bypass them to crowd into the regional referral centers.

"Rural" Hospital

Demonstrating "Point-of-Care" Ultrasound in the ED

The remainder of the week was spent intubating patients in the operating rooms. For the most part, the tubes were easier than in America, which I think is in large part due to the thinner body habitus of patients in China; however, there were also a few difficult patients. One that stands out in my mind was a poor 15 year-old kid with TB and Pott’s disease and numerous abscesses on his back that needed to be opened up and drained. Since the patient could not be placed on his back, he had to be intubated in the lateral decubitus position. The week ended with a night out with a few of the anesthesia attendings to catch a local movie (The Vanishing Bullet – I give it 4.5/5 stars) and hotpot.

I spent my last weekend in China going to SongXiao Qiao, a collection of stalls and stores selling “antiques” and artwork. Since it was my last weekend, I felt I should really take advantage of the little time I had left to explore the city, as I had spent my free weekends outside of the city. So, I planned a walking tour to get to the city, which was about an hour away. On my way back, I ran into the infamous fainting vagrant.

The Fainting Vagrant

The fainting vagrant is a young man in his twenties that found his way to Chengdu a few weeks after I did. I first heard about him during a morning report checkout, when the chief resident complained about how she had to respond to 5 calls the previous day on this one person. Like most vagrants, he did not have any money, nor did he have his government issued ID giving him a hukou (a kind of residency permit that, among other things , gives you access to social services in your area). Therefore, he was not eligible for any government programs either. He would have fainting spells during which he would clutch at his chest. Concerned bystanders would call the ambulance. When the ambulance arrived, he would refuse to go to the hospital. This would happen 5, 6, 7 or more times a day and always play out the same way. As I was walking home that last weekend, I ran into a crowd surrounding this person. Wanting to see whether the situation would play out as I had heard, I hung around and, sure enough, someone in the crowd of bystanders called 120 (911) and 8 minutes later (pretty good response time), an ambulance rolled up and one of the chiefs came out, tried to examine the patient despite his refusal to cooperate, and eventually, after 30 minutes of attempting to convince him to come to the hospital, went back empty-handed.

Cost of Healthcare

Intubation in the E-ICU

"Hey, Zubair, want a tube?" one of the chiefs asked me.

"Of course, who needs one?"

"Sit tight, we're still waiting for the family to decide if they want to pay for it."

That was a conversation I had in China that I have never had in America, and it highlights one of the fundamental differences between the two countries with regards to who bears the burden of healthcare. Now, before I continue, let me first say that in cases of critically ill patients who come in, the West China ED initiates life-preserving treatment including code drugs, resuscitation, and intubation for patients prior to finding family members and sorting out payment details. This particular patient was unique in that he was a terminally ill patient near the end of life, and the real question was whether the family wanted to pay for heroic measures in what might have been a futile resuscitation attempt leading to a prolonged vent wean if he made it to the ICU (In America, we call this their code status). However, the way in which this scenario is framed as a cost of futile care issue constrasts sharply with the attitude in America, where discussion of cost (and by extension resource allocation) is almost a taboo discussion. This particular patient’s code status would have been couched in the language of what his wishes would be. If a patient came to the ED with respiratory failure and no advance directives dictating his code status in America, we would intubate him or do whatever we felt necessary , almost always without considering the costs of the procedures or tests. For one thing, we have EMTALA laws that essentially mandate every patient get a work up and any life saving treatment necessary. Furthermore, for many of us who have grown up in or trained in America, it is incomprehensible to withhold therapeutic interventions or even diagnostic tests from a patient who obviously needs it. The reasons for this are multifactorial. First and foremost, I feel that we as a society in America have come to view healthcare as a right. Thus, the preservation of life trumps everything else, and the patient’s ability to pay is not usually something that is part of the decision making process. The Chinese way is as a fee for service model where a patient’s family is responsible for paying prior to services being rendered, whether they are administration of medications, blood draws for tests, or, as in the case above, intubations. The way it works is the physician writes a prescription for a medicine, test, or imaging study that needs to be done. A family member then takes this prescription to a cashier, and brings back the medicine or a receipt that allows for the medicine to be given or the test to be done. Another consideration I feel contributing to this model is the relative wealth of the U.S. versus China. Many physicians in China have told me that the way we practice medicine in America would bankrupt hospitals in China. Hospitals in America stay afloat and remain quite profitable through a variety of methods, such as cost shifting and government reimbursements for taking care of the indigent.

Hospital Pharmacy

What do I think of these two different practices? As a physician who has trained in the American system, I feel uncomfortable with the thought of withholding life-saving treatment from someone simply as a result of their inability to pay. This would have implications on the way we practice as well; for example, instead of relying on the gold standard tests for diagnosis or rule outs, we would have to tailor each patient’s management based on their financial status, and the same with regards to their choice of medications. These alternative tests or medications may not have the same sensitivities/efficacy as more expensive alternatives, and may ultimately result in different standards of care. I feel this would go against most Americans’ ideal of egalitarianism (though many would argue that this scenario is, in fact, already an unspoken reality). Further, there is the concern that someone would be allowed to die simply because family was not around, for example, in cases of trauma where the next of kin is often not immediately identifiable. All things considered, I feel a very compelling argument can be made for a fee for service model. The biggest benefit I think this type of model would offer is more judicious use of resources. This is obviously a bigger issue in the developing world than in first world nations, but even in America, I think most doctors would agree that we order too many unnecessary tests. Of course this would have to go hand-in-hand with changes in the litigious environment of medical practice and tort reform. Speaking of, is the practice of medicine in China fraught with fear of litigation? Yes and No. Throughout my rotation in China, I often witnessed attendings reminding residents to document carefully and obtain consents for everything in case there was a bad outcome. One week, I even witnessed a local camera crew covering the poor outcome of a patient’s case. At the same time, the legislative process does not seem as “developed” as in America and residents in China recount numerous cases of family members taking matters into their own hands and physically attacking doctors. A few years ago, an ENT physician at West China was stabbed after a patient was unhappy with his surgery. Another case involved a medical student that was fatally stabbed when she was at the wrong place at the wrong time and a disgruntled family member went on a rampage. Even while I was there, I witnessed multiple confrontations between overworked doctors and stressed-out family members.

Summary

My summer in China was a phenomenal once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and I am greatly indebted to the residency program at Palmetto Health Richland that made it possible for me to go and my fellow residents who pulled extra shifts in order to keep the ED covered while I was gone. I am also very grateful to my gracious hosts at West China Hospital in the Emergency and Anesthesiology departments who not only provided me with my housing while there, but also a great learning experience.

Other activities

Visiting the Panda Reserve

Pandas are deceptively good at climbing trees

Medical School Library

Medical School Clocktower

With our host 何亚荣 and Jonny Yadlowsky, medical student from the US after climbing Qingcheng Mountain

Outside Dujiangyan, a famous irrigation project in Chengdu, with a statue of Zhuge Liang, a famous historical figure in China

Making candy

Chinese Ear Massage

Pulled noodles

Caught in the middle of a demonstration; these riot police were responding to a demonstration outside of a Japanese department store over an incident over disputed islands between China and Japan.

Joe Kim, a fellow PGY3 EM resident, was finishing up his rotation in South Korea around the same time I was finishing up my rotation in China. We met up in Tokyo and climbed Mt. Fuji!

Temple in Tokyo

Magnificent view from Mt. Fuji

Back to Locations List

Back to Locations List